I've just updated this post, to replace the pictures of buildings in Pompeii that I'd pulled of the Internet with my own photos (and to correct the misidentification on a tag of the theatre at Pompeii as that of Ostia.

Can't do anything about Nimes, though, as I've never been there, and have no other good pictures of large amphitheatres that aren't the Colosseum.

This is my blog for posting material of academic interest (to me). Expect to see stuff about Greek and Roman history, archaeology, Classical literature, the Ancient Near East, historical films, teaching, the reception of the Classics in science fiction, the abuse of history, science fiction criticism, Doctor Who, and occasionally other historical stuff, or just things that I'm interested in. Expect spoilers at all times.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

Friday, April 21, 2006

Headless Romans

I didn't watch tonight's Timewatch, 'The Mystery of the Headless Romans', as closely as I'd intended. I thought I was taping it to watch properly later, but unfortunately my video decided not to work properly, and this being BBC2 rather than BBC4, there's no quick repeat planned (though there might be a signed version in the wee small hours some time).

However, from what I did manage to catch, I wasn't too impressed. It seemed to be ploughing the common furrow of 'Weren't the Romans awful?' Now, I'm all for not romanticizing Rome, but I'm not keen on distorting the evidence to make them seem worse than they were. And this programme seemed to do this. For instance, it was stated that Septimius Severus pursued a scorched earth campaign in Scotland, and quoted something he said in support of this.

Now, all well and good, except that our source for this, Cassius Dio 77.15.1, places this remark after Severus had returned from campaigning and was now south of Hadrian's Wall. He had made terms with the Caledonians and Maeatae, the tribes who lived in Scotland. When he had departed, in AD 210, the Maeatae revolted, and it was only then that Severus issued the instruction to kill everyone. It was not, as the programme implied, his policy from his first invasion of Scotland in AD 208.

Nor did I care for the depiction of the relationship between Severus' sons, Caracalla and Geta. Caracalla was portrayed as a nasty man, out to eliminate his brother to become sole ruler. Fine, I have no problem with that. What I have a problem with is the implication (by omission) that his brother Geta was somehow better. He has a better press, because he befriended the literary elite in Rome, but reading between the lines would suggest that he was almost as nasty and ambitious as his brother.

Finally we come to the very sensible Tony Birley's theory about who the headless Romans in York might be, enemies of Caracalla dispatched after Severus' death. That is not implausible, but the narration implied that these included prominent people such as Severus' chamberlain Castor and Caracalla's tutor Euodus. Well, yes, we know that Caracalla had these people killed, even before Geta's murder, though many more happened after. But we don't know that these executions took place in York, or even in Britain. All we can say is that Dio implies that they didn't take place in Rome. On the open2.net forum someone has rightly pointed out that the facts that none of these bodies were over forty, and some had been shackled for some time, do not sit easily with the what the narration implied about swift executions of Severus' secretariat. So it's wrong to say, as the programme does, that we know who these people in the graveyard were - we only have a theory about who they might have been.

The portrayal of the tutor Euodus is a bit perplexing. For a start, there's an implication that Euodus was executed for counselling reconciliation between Caracalla and Geta - but as far as I can tell, it was another tutor of Caracalla, the senator Lucius Fabius Cilo, who did that. I'm not sure what the evidence for Euodus being from North Africa is either, though since Septimius was from Libya himself, and tended to surround himself with others from that area, it's certainly possible. But the actor playing him is an African of sub-Saharan descent (as was a actor portraying an African soldier), and I'm not sure that's right at all. But here we get into the knotty problem of the inability to distinguish between northern and sub-Saharan Africa, which has led to Septimius Severus appearing on a list of great Black Britons (he was neither black nor British). Curiously, in this programme Septimius was portrayed as a white European, suggesting an ethnic divide between him and the tutor Euodus which, if the latter was from North Africa, was almost certainly not there.

Unfortunately I don't have access to Tony Birley's Septimius Severus: the African emperor. I suspect I need to have a look to see what he says about some of these matters.

Overall, not very impressive for the BBC's flagship history programme, and one where supposedly the Open University works in partnership, to produce something so indifferent to the order in which events actually occurred.

Let no one escape sheer destruction, no one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, if it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction. [This is apparently a quotation from some literary work, but I don't know what it might be.]

Now, all well and good, except that our source for this, Cassius Dio 77.15.1, places this remark after Severus had returned from campaigning and was now south of Hadrian's Wall. He had made terms with the Caledonians and Maeatae, the tribes who lived in Scotland. When he had departed, in AD 210, the Maeatae revolted, and it was only then that Severus issued the instruction to kill everyone. It was not, as the programme implied, his policy from his first invasion of Scotland in AD 208.

Nor did I care for the depiction of the relationship between Severus' sons, Caracalla and Geta. Caracalla was portrayed as a nasty man, out to eliminate his brother to become sole ruler. Fine, I have no problem with that. What I have a problem with is the implication (by omission) that his brother Geta was somehow better. He has a better press, because he befriended the literary elite in Rome, but reading between the lines would suggest that he was almost as nasty and ambitious as his brother.

Finally we come to the very sensible Tony Birley's theory about who the headless Romans in York might be, enemies of Caracalla dispatched after Severus' death. That is not implausible, but the narration implied that these included prominent people such as Severus' chamberlain Castor and Caracalla's tutor Euodus. Well, yes, we know that Caracalla had these people killed, even before Geta's murder, though many more happened after. But we don't know that these executions took place in York, or even in Britain. All we can say is that Dio implies that they didn't take place in Rome. On the open2.net forum someone has rightly pointed out that the facts that none of these bodies were over forty, and some had been shackled for some time, do not sit easily with the what the narration implied about swift executions of Severus' secretariat. So it's wrong to say, as the programme does, that we know who these people in the graveyard were - we only have a theory about who they might have been.

The portrayal of the tutor Euodus is a bit perplexing. For a start, there's an implication that Euodus was executed for counselling reconciliation between Caracalla and Geta - but as far as I can tell, it was another tutor of Caracalla, the senator Lucius Fabius Cilo, who did that. I'm not sure what the evidence for Euodus being from North Africa is either, though since Septimius was from Libya himself, and tended to surround himself with others from that area, it's certainly possible. But the actor playing him is an African of sub-Saharan descent (as was a actor portraying an African soldier), and I'm not sure that's right at all. But here we get into the knotty problem of the inability to distinguish between northern and sub-Saharan Africa, which has led to Septimius Severus appearing on a list of great Black Britons (he was neither black nor British). Curiously, in this programme Septimius was portrayed as a white European, suggesting an ethnic divide between him and the tutor Euodus which, if the latter was from North Africa, was almost certainly not there.

Unfortunately I don't have access to Tony Birley's Septimius Severus: the African emperor. I suspect I need to have a look to see what he says about some of these matters.

Overall, not very impressive for the BBC's flagship history programme, and one where supposedly the Open University works in partnership, to produce something so indifferent to the order in which events actually occurred.

Rosemary Sutcliff

Discovery of yesterday was a couple of blogs about Rosemary Sutcliff. One is written by Anthony Lawton, her godson and (I believe) literary executor. It's updated irregularly, but it did provide a link through to a discussion of her linked Roman Britain novels, that I found quite interesting (if sometimes a bit inaccurate).

The other is more regularly updated, and produced by fans. Treasures found therein include a teacher's guide to Sutcliff's novels, and another article on the novels linked by the Dolphin ring (in three parts: I, II and III).

I learnt a lot of stuff I hadn't known in these pieces, such as the fact that The Shield Ring, in terms of internal chronology the last in this sequence, set in the Lake District in the time of Henry I (and which is slightly mixed up in my mind with the Norman novels of Jean Plaidy, which I read at about the same time), was actually written after The Eagle of the Ninth, but before any of the others.

I was trying to figure out why I hadn't read either Frontier Wolf or Sword Song, both of which are connected with the sequence. I haven't read all her works by any means, but I did make an effort to track down all of those with the Dolphin ring in them. But as I recall now, I was doing this in 1978-79, and these two novels hadn't yet been written.

There is one other novel in the sequence I haven't read: Sword At Sunset, her historical Arthur novel, and the only book she wrote for adults rather than for children. I did try. But, though Sutcliff said there was no difference between her writing for children and for adults, that's not how it felt to me. I found the prose in Sword at Sunset turgid and impenetrable.

Final note: the IMDB entry for the BBC TV version of Eagle of the Ninth makes no mention of Sutcliff. Naughty.

The other is more regularly updated, and produced by fans. Treasures found therein include a teacher's guide to Sutcliff's novels, and another article on the novels linked by the Dolphin ring (in three parts: I, II and III).

I learnt a lot of stuff I hadn't known in these pieces, such as the fact that The Shield Ring, in terms of internal chronology the last in this sequence, set in the Lake District in the time of Henry I (and which is slightly mixed up in my mind with the Norman novels of Jean Plaidy, which I read at about the same time), was actually written after The Eagle of the Ninth, but before any of the others.

I was trying to figure out why I hadn't read either Frontier Wolf or Sword Song, both of which are connected with the sequence. I haven't read all her works by any means, but I did make an effort to track down all of those with the Dolphin ring in them. But as I recall now, I was doing this in 1978-79, and these two novels hadn't yet been written.

There is one other novel in the sequence I haven't read: Sword At Sunset, her historical Arthur novel, and the only book she wrote for adults rather than for children. I did try. But, though Sutcliff said there was no difference between her writing for children and for adults, that's not how it felt to me. I found the prose in Sword at Sunset turgid and impenetrable.

Final note: the IMDB entry for the BBC TV version of Eagle of the Ninth makes no mention of Sutcliff. Naughty.

Fighting the blurring of terminology

For the benefit of travel book writers, tour guides, tourists and students everywhere (especially those having to do with the monuments of Roman Asia) ...

This

is a theatre. The seating forms a semi-circle, or slightly more, around the performance area.

This

is an amphitheatre. The seating forms an oval around the performance area.

The terms 'amphitheatre' and 'theatre' apply to two distinct types of building, and are not interchangeable, even if gladiatorial games were held in both.

And while we're at it, this

is not a 'colosseum' (or 'coliseum').

This

is the Colosseum. There is only one.

(This inspired by my recent trip to Turkey, where I found theatres at Side, Aspendos and Fethiye all labelled as 'amphitheatres', even in respectable volumes like the Dorling-Kindersley Turkey guide. They're not. There was even a little open air theatre in the hotel we were staying in, and that too was labelled as 'amphitheater'. Yet curiously, I saw no fights or wild beast hunts all week.)

is a theatre. The seating forms a semi-circle, or slightly more, around the performance area.

This

is an amphitheatre. The seating forms an oval around the performance area.

The terms 'amphitheatre' and 'theatre' apply to two distinct types of building, and are not interchangeable, even if gladiatorial games were held in both.

And while we're at it, this

is not a 'colosseum' (or 'coliseum').

This

is the Colosseum. There is only one.

(This inspired by my recent trip to Turkey, where I found theatres at Side, Aspendos and Fethiye all labelled as 'amphitheatres', even in respectable volumes like the Dorling-Kindersley Turkey guide. They're not. There was even a little open air theatre in the hotel we were staying in, and that too was labelled as 'amphitheater'. Yet curiously, I saw no fights or wild beast hunts all week.)

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Cocaine and Egyptian mummies

I'm sure that there will be some people reading this who will be able to answer the following question, brought to mind by something I saw in another journal. What's the current scholarly consensus (if any) on the presence of cocaine and nicotine in Egyptian mummies? I'm no expert on this, but I remember from Channel 4's programme Mystery of the Cocaine Mummies (transcript here) that some of the evidence isn't as easily dismissed as most crackpot theories. Which would seem to suggest that there must have been some form of trans-Pacific trade, as these products are only available in the Americas. However, I don't think, as most people who accept this evidence seem to, that this necessarily means Egyptians went to South America, or South Americans went to Egypt, or that either were aware of the other. Surely it needs no more than for there to be interlocking trade connections across the Pacific. I certainly don't see any difficulty in assuming that there was trade from Egypt down the Red Sea and across the Indian Ocean. The problem is the eastern end, but Thor Heyerdal's work with Kon-Tiki would seem to suggest that it's not technologically impossible. So the material could potentially have crossed the Pacific, but by the time it reached Egypt, it would have become unprovenanced. Anyone know any better?

I'd have a look at Wikipedia, but it seems very ill today.

I'd have a look at Wikipedia, but it seems very ill today.

Discussion of sf models

I'm just adding a link to Alun's discussion of my sf models paper over on Archaeoastronomy, not for the sheer egoboo of it (look, people are talking about me!) but because I'm going to need to find it when I come back to revise the text.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Mary Renault

I've just watched a very interesting documentary on BBC Four on Mary Renault. It worked hard to put Renault's work in the context of movements in Classical education in the 1950s, and managed to pack much more into an hour than most history programmes do - at one point I looked at the clock and saw it had only been going on for twenty minutes, which I couldn't believe given what they'd managed to say.

The Usual Suspects (Tom Holland, Bettany Hughes, etc.) were among the talking heads, but there were also contributions from professional academics (and friends of mine) Gideon Nisbet and Nick Lowe. I shall clearly have to do something about reading more of Renault than just The Praise Singer. Curiously though, no mention of her one non-fiction book, The Nature of Alexander.

The programme is repeated at 00:50 tonight, and will no doubt appear on BBC2 soon. Watch for it.

The Usual Suspects (Tom Holland, Bettany Hughes, etc.) were among the talking heads, but there were also contributions from professional academics (and friends of mine) Gideon Nisbet and Nick Lowe. I shall clearly have to do something about reading more of Renault than just The Praise Singer. Curiously though, no mention of her one non-fiction book, The Nature of Alexander.

The programme is repeated at 00:50 tonight, and will no doubt appear on BBC2 soon. Watch for it.

More fame

At the Eastercon (the British National SF Convention) this weekend, I was on a panel on historical fantasy with Susanna Clarke, author of the best-selling and Hugo-winning Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. When we met before the panel, she asked me if I was the Tony Keen who had a Classics website, to which of course I said yes.

It's silly, I know, but this sort of thing still brings me a bit of a thrill.

It's silly, I know, but this sort of thing still brings me a bit of a thrill.

Three books read

Read because Kate was devouring my Sutcliff collection, and I hadn't read this one. Written in 1978, it's a lesser Sutcliff, without the fine writing seen in The Silver Branch or The Lantern Bearers.

I'm not sure that I believe that the Iceni were matrilineal, or that there were contingents in Boudicca's army from tribes as far away as the Brigantes, but this is a work of fiction, so Sutcliff is entitled to suggest that this was the case, as long as she doesn't completely violate what little is known for certain. Arguably she does this when she has the sack of Verulamium take place at almost the same time as that of Londinium, and carried out by a separate section of Boudicca's army. But I think she does this to speed the novel along, and also because her conception of the campaign has the Romans wintering in Chichester in the hope of getting reinforcements from Gaul. In any case, any errors in this are as nothing compared to, say, Eagle of the Ninth, where much of the plot depends on serious misunderstandings of the way the Roman army worked.

As the reviewer for Amazon.co.uk, one David Langford, opines, Sutcliff does not spare her juvenile readers some of the horrors of the Boudiccan revolt, though she does find a circumlocution for 'rape', and the fate of the women of Colchester (hung up with their breasts cut off) is merely hinted at.

Read to give some theoretical support to my own writings on the reception of classics in modern sf. It's a useful little volume, though I wish Lorna would use more commas. There were a number of times where I had to read sentences more than once to understand what she was actually saying.

Finally got around to this, which I read for obvious reasons. As with most sf, it's far too long (and even at the end of 600-plus pages he story remains half-complete, with only two of the novel's three strands have been linked). But overall it works. At first the future Earth and future Mars stories seemed a distraction from the account of the Trojan War, but soon they gain momentum, and actually become more enjoyable. Many questions (how does this all link in with Homer? What are the gods?) remain for the sequel, Olympos.

Labels:

boudica,

boudicca,

reception,

Rosemary Sutcliff,

sf,

Trojan War

Thursday, April 13, 2006

I, Cartagia

My paper from the academic track at last year's Worldcon, 'I, Cartagia: a mad emperor in Babylon 5 and his historical antecedents', is now up on the SF Foundation website.

http://www.sf-foundation.org/publications/academictrack/keen.php

http://www.sf-foundation.org/publications/academictrack/keen.php

Monday, April 10, 2006

The 'T' stands for Tiberius: models and methodologies of classical reception in science fiction

[The following is a paper I delivered at the 2006 Classical Association Conference in Newcastle. I had to edit it down to fit a twenty-minute slot, and what follows is the full-length version, with some changes as a result of points made in the subsequent discussion. I've also only included those of the illustrations I used in the lecture that are significant for points I'm making. I apologize for the fact the there are no links to the notes - this is beyond the frontier of my HTML expertise. Comments and corrections are warmly invited.]

This paper forms the introduction to a planned larger work looking at a number of different aspect of the way in which sf uses the Greek and Roman Classics. I shall start with two parallel, interrelating introductions.

Introduction number one: Studying the way that Classical antiquity is received in modern works of art and literature changes not only the way we look at those works, but also how we look at the source material. For instance, many of my thoughts on what Athenian dramatists were actually trying to say have been formed or amplified through observation of contemporary interpretations. Sometimes the insights are quite unexpected - it wasn't until I read Ulysses, and saw what Joyce was trying to do, to find the exact combination of English words that conveyed the precise nuance that he desired, that I finally understood what Thucydides was trying to do with Greek. And so it is with science fiction.

Introduction number two: I am aware that in looking at science fiction, I am in danger of being perceived to be engaged in the study of the 'banal and quotidian' that Charles Martindale condemned in the Reception debate at the 2005 Classical Association Conference in Reading. The frivolous response to such a charge would be to say that I'm just using this as an excuse to read all the books and watch all the television and films I would read and watch anyway, and call it 'research'; but that would be rather to denigrate my own work, and potentially that of everyone else working in reception. So instead I shall defend myself from such a charge in two rather more serious ways. First of all, sf is not intrinsically banal and quotidian. (I'm not going to argue this - it just isn't.) Secondly, even if it was, it wouldn't matter. Martindale's objection, in my view, confuses aesthetic value with cultural significance. I have no objection to people making aesthetic judgements, and make plenty of my own. But any such judgement I or others might make is unrelated to whether the piece of work judged is worthy of study in terms of its reception of Classical ideas. Put simply, one can say that Gladiator is a poor film, but it doesn't follow from such an opinion that Gladiator is not important. If most people are getting their experience of the ancient world through the banal and quotidian, then it is the banal and quotidian that must be studied.

Let us start then, as an example of how sf receives the classics, with Tiberius. Not the second Roman emperor, stepson and adopted son of Augustus; but arguably the single most iconic figure in all of science fiction, Star Trek's James Tiberius Kirk.

Captain Kirk's middle name took a long time to be established. Indeed, when he was first introduced, in the second pilot of Star Trek, 'Where No Man Has Gone Before' (1966), his middle initial is shown on a gravestone as 'R.' This detail had been forgotten by the next time someone wanted to give Kirk's middle initial, and so it became 'T.' But what this stands for remained unknown throughout the original run of Trek.

That it is 'Tiberius' was finally established in 1974, in an episode of the animated series of Star Trek that followed the original - 'Bem', written by David Gerrold. Now, almost everything that happened in the animated episodes is considered non-canonical for subsequent Trek productions. That is, they are never referred to, and no attempt is made to avoid contradicting them. But, curiously, the detail of Kirk's middle name does get into the Star Trek canon.[1] This suggests to me that it was series creator Gene Roddenberry's notion, rather than writer Gerrold's.

In the novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), there is a preface made out to be by James Kirk himself. (The novelization is credited to Roddenberry, but reportedly is actually by Alan Dean Foster, so what we have here may be Foster pretending to be Roddenberry pretending to be Kirk.) In that preface, Kirk shows his Classical credentials by stating that he has come to be seen as a new Ulysses, and that he is uncomfortable in the role. He also explains his name:

Anybody who has read Suetonius' Life of Tiberius, or is familiar with I, Claudius or Tinto Brass' 1979 film Caligula, will know that Tiberius was notorious for the quantity, variety and invention of his sexual perversions. Several questions therefore clearly arise. What exactly was it about Tiberius that so fascinated Samuel Kirk? Do Samuel Kirk's interests, together with James being named after his mother's 'love instructor' (whatever one of those is), explain the voracious heterosexual appetite of the grandson?[2] But above all, what were they thinking?

I'd now like to examine some theoretical models. Greco-Roman elements (or indeed elements from any historical culture) can be used in science fiction in a number of different fashions. What follows is a rough framework for discussion, and is not meant to be a rigid categorization of use of Classical elements, but a broad heuristic tool. It is a model, and like most models, breaks down when subjected to rigorous examination. And I remain firmly in the camp of those who would rather break the model than break the evidence.

Retellings

Straight retellings of mythological tales don't really interest me for the purposes of this paper or for the larger work. These stories, such as Weight (2005), Jeanette Winterson's recent reinterpretation of the Atlas myth, belong in the genre of fantasy rather than sf (where they do not, as David Gemmell's bestselling Troy: Lord of the Silver Bow [2005] does, belong in historical fiction). Of course, the boundaries between sf and fantasy are frequently blurred, as anyone familiar with the works of China Mieville will know. But I don't have time to go into a detailed discussion of the definitions of both genres, which would in any case only be my definitions, and would not necessarily be recognized by everyone. Let me just say that, in my view, science fiction assumes a rational explanation to everything, no matter how fantastic it might seem or how pseudo-scientific that explanation might be, whilst fantasy assumes the irrational. So, gods that are in fact super-powerful aliens are science fiction, gods that are gods belong in fantasy. And to this latter category we must consign, as well as retellings, new tales featuring mythological characters, such as the various different film and television series featuring Hercules, stories featuring new characters in a mythological past, such as Xena: Warrior Princess, tales of the fantastic set in historical antiquity, such as Gene Wolfe's Latro in the Mist novels,[3] or even tales of the gods still walking amongst us, such as the episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, 'Yes Virginia, There is a Hercules' (1998) and 'For Those of You Just Joining Us' (1999), where there is no science fictional element.[4]

What are the truly science fictional uses?

Allusion

First is simple allusion, brief references to ancient history or literature that are not particularly central to the story being presented. This can manifest itself in titles, without carrying any deeper message. Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1934 story 'A Martian Odyssey', that later gave its name to a collection of his stories from 1949, has little in common with Homer's epic poem beyond both being about long journeys. The same appears to be true, at least on the surface, of Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.[5]

Such title allusion can sometimes be not to the Graeco-Roman originals, but to other receptions, such as when Eando Binder (Earl and Otto Binder) entitled their short story 'I, Robot' (Amazing Stories, January 1939), referring to Robert Graves' classic 1935 novel I, Claudius. (The title was later stolen by Isaac Asimov's publisher for the first collection of Asimov's own robot stories in 1950, much to Asimov's annoyance, as he preferred Mind and Iron.)[6]

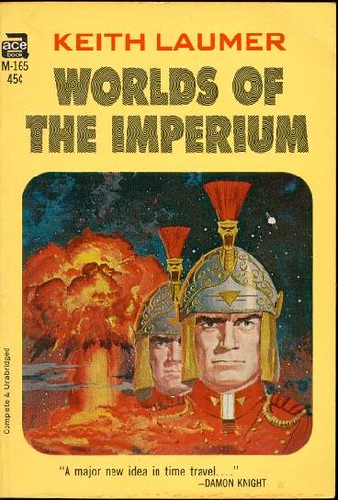

Allusions may be in the sf work in the form of names,[7] such as James Tiberius Kirk already mentioned; or the use of terms like 'imperium', as in Keith Laumer's Worlds of the Imperium, where the Imperium is the name of the principal state in the story.

In the latter case, as seen above, the name of that state may have inspired cover artist Ed Valigursky to put Roman-style helmets on the figures illustrated.[8]

More substantially, classical allusion may be used to comment on the situation in which the characters find themselves. One such may be found in an episode of the sequel to Star Trek, Star Trek: The Next Generation, 'Best of Both Worlds' (1990). Faced with the Borg, an implacable enemy that may destroy the Federation, Captain Jean-Luc Picard muses on whether this was how the emperor Honorius felt in AD 410 as the Goths descended upon Rome. The purpose of the allusion is not always so immediately clear. In Ken MacLeod's novel The Stone Canal (1997), two drunk men sit by the Forth Estuary and talk about how this is where Rome stopped (a reference in keeping with the theme of the Newcastle conference, 'On The Frontier'). The immediate significance of this isn't apparent on first reading, though there does seem to be something of a meme in recent British literary sf of scenes with two blokes drinking and talking about the Roman empire - in an appendix I've included a similar scene from Stephen Baxter's Coalescent (2003), though there it's more obviously relevant, as the story begins in early fourth century AD Roman Britain. This meme may go back to the American author Philip K. Dick, whose characters, as the sf critic Andrew M. Butler has shown,[9] often muse on Rome - even before Dick's (presumably drug-induced) visions of being himself transported back to the late first century AD.

However, MacLeod is a man with interests in classical antiquity - he is well-versed in the Epicureans and Stoics and the works of Lucretius and Marcus Aurelius[10] - so the reference in his case is unlikely to be gratuitous. As one reads The Stone Canal further, it becomes clear that the novel is very interested in the limits of empire, and that may be why MacLeod has included this scene.

These allusions make important points about popular understanding of antiquity. Classicists know that Honorius was actually in his capital Ravenna at the time of the sack of Rome, but the writers of Star Trek clearly don't. Ken MacLeod probably does know that to say that Rome stopped at the Antonine Wall is an oversimplification that ignores the Flavian, Antonine and Severan penetrations further into Scotland; but his characters, two drunk blokes talking shite, can't necessarily be expected to have that knowledge.

Appropriation

A step up from allusion is appropriation, the depiction of a society or individual which has in some method consciously modelled itself upon Greco-Roman (or other historical) precedents. For examples of this I turn once again (but for the last time) to Star Trek. A non-classical instance is the episode 'A Piece of the Action' (1968), in which a planetary culture is encountered that imitates Chicago mobsters of the 1930s. 'Plato's Stepchildren' (1968) provides a classical example. This episode was controversial in the United States because it reportedly featured the first depiction of an interracial kiss on network television, and was banned in the UK, probably because of a sado-masochistic whipping scene that suggests Jim Kirk may know more about his grandfather's fascination with Tiberius than he's letting on. But my interest in it is because it features a society that has allegedly modelled itself upon Plato's ideal state. However, I doubt Plato ever envisaged his philosopher kings as being in addition super-powerful psychokinetics, and I also doubt that the episode's writer, Meyer Dolinsky, had read much Platonic philosophy - certainly there's little sign of it in the episode.[11]

Allusion aside, appropriation is far and away the most plausible form of reception of the Classics in sf, as it is simply imagined societies and individuals doing what real historical cultures, such as Napoleonic France or Fascist Italy, did. However, it is also one of the least common. Nazis seem to be much more popular for this sort of story (q.v. Star Trek, 'Patterns of Force' [1968]).

Interaction

More frequent is what I call, perhaps somewhat misleadingly (and not necessarily in honour of the 2005 Worldcon), interaction. This covers stories actually featuring the cultures or individuals (real or imagined) of the Classical past, or some continuation of the same. The locus classicus for this sort of tale, of course, is the long-running BBC television series Doctor Who, a show based around the concept of travel in time and space (in the unlikely event that there's any one reading this who doesn't know that). And indeed, the Doctor has on his travels visited Rome at the time of Nero, the Trojan War, and the pre-Hellenic Aegean in the age of Atlantis, and encountered displaced Roman soldiers and creatures of Classical mythology; and more such stories are to be found in spin-off novels and audio dramatizations.[12] But interaction can be seen elsewhere. There are two consecutive 1974 stories from ITV's 1970s rival to Doctor Who, The Tomorrow People. In the second, A Rift In Time, the Tomorrow People travel back to the Roman period (and inadvertently interfere in human history by bringing about the Industrial Revolution a thousand years too early, forcing them to go back and put it right). In the first, The Blue and the Green, more unusually, they find themselves up against entities which promoted the rivalry between factions in the Roman circus. For a literary example, Stephen Baxter's Coalescent, already mentioned, concerns a secret society whose origins lie in fifth-century AD Rome. Or one might encounter a Princess who comes from among the Amazons, who have kept themselves sealed off from Man's World for millennia (the origin of William Moulton Marston's superheroine Wonder Woman).

It is in these sorts of stories that I think one can start to see what science fiction can do that other forms of reception perhaps can't as easily.

As an example, I take Helen of Troy. Casting Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, is very difficult for a naturalistic stage, film or television production, since beauty is such a subjective concept. My favourite exemplar of this is Michael Cacoyannis' film of Euripides' Trojan Women (1971). Cacoyannis cast Irene Pappas in the role, who was his wife, and therefore his idea of perfection in female beauty. But she's not mine, especially not when the same film features Vanessa Redgrave at her most radiant in the role of Andromache. When Doctor Who tackled the Trojan War, in a 1965 story called The Myth Makers, writer Donald Cotton solved this problem simply by never bringing Helen on screen, and thus her appearance always remains in the viewers' imaginations. Now, it might well be said that any writer of historical fiction could pull the same trick, but I'm not sure that a non-sf treatment would think to exclude Helen in this way. More likely they would take the approach of Eric Shanower's series of graphic novels Age of Bronze (1998 onwards), where Helen's supreme beauty is a rumour spread by Odysseus to motivate the Greek army. This is a realistic approach, but for me lacks the elegance of Cotton's trick. However, the trick is not unique to sf, as Hector Berlioz in the nineteenth century omitted Helen from the onstage cast of Les Troyens, and it may well have been this which gave Cotton the idea.

If the example of Helen is something that genres other than sf can do, then a convincing portrayal of the Greek gods is much more sf's province. Nick Lowe has observed[13] that almost all recent treatments of the Trojan War have excluded the direct involvement of the gods, either through eliminating them entirely or through segregating them from the principal human characters. This is true not just of Wolfgang Petersen's film Troy (2004), which was much criticised for this aspect (as well as others),[14] but also of Shanower's Age of Bronze and Gemmell's Troy, and (as far as I am aware) of Lindsay Clarke's The War At Troy (2004) and Valerio Massimo Manfredi's The Talisman of Troy (2004). According to Lowe, the only recent treatment of the Trojan War to successfully integrate the gods is Dan Simmons' sf novel Ilium (2003; the sequel, Olympos appeared in 2005). There advanced technology takes the place of the divine power that seems to embarrass other writers interested in writing historical adventures; the gods' Mount Olympos becomes Olympus Mons on Mars.

Into this category I would also put stories dealing with alternate histories (or 'counterfactuals' for authors worried that they might otherwise be accused of writing science fiction), e.g. ones where Rome never fell. The two characters in Baxter's Coalescent are discussing what might have happened had the western Roman empire survived, and such a notion is at the heart of Robert Silverberg's Roma Eterna[15] (2003), and of Sophia McDougall's recent Romanitas (2005). In Silverberg's collection of stories, the combined factors of the Jewish Exodus from Egypt ending in disaster, and a different emperor succeeding Septimius Severus, lead to the survival of the Roman empire past the twentieth century.

Alternate history, to my mind, makes us ask new questions of the ancient world. Classicists often look at, for instance, how the Roman empire worked, but less often, I feel, at questions of whether the Roman empire was a good thing or not. Would we want it to survive? Would we want to live in a state which, though it brought order and peace, was a slave-owning military dictatorship where freedom to criticize the government was severely limited? Looking at alternate histories prompt us to ask such questions, even if they were not always in the original authors' minds.

Sometimes the connection between alternate history and scholarship can be even closer, and alternate history can take on the form of academic discourse, as in Neville Morley's brilliant paper to the 1999 Classical Association Conference, subsequently published in 2000 in Greece and Rome - 'Trajan's engines', a scholarly examination of technological feats the Romans never actually achieved.[16] So well done is this that some were fooled, and it still crops up in some online bibliographies of writing on Trajan.

Borrowing

My fourth category, borrowing, is much like appropriation, in that elements of Classical antiquity are used to build an imagined society. The difference is that in this case only the author and audience are aware of the origins of features of the imagined culture - the members of the culture themselves are not, and cannot be, for there is no connection between them and Earth's antiquity.

Sometimes this borrowing can be as minor as simply the use of nomenclature. Greek and Latin can be a reliable source of names that are sufficiently unfamiliar to a readership to be credibly alien, yet retain the ring of something that might actually be spoken, rather than something that an author has made up off the top of his head. This is especially the case where a name does not conjure a particular individual in the popular imagination.[17] M. John Harrison takes the Roman name of Wroxeter, Viriconium, for a fictional city at the centre of a sequence of what are strictly speaking fantasy stories, but ones with a strong sf undercurrent.[18] In the paper that formed the other part of the panel in which the current paper was presented, Amanda Potter commented on the use of names like Apollo, Athena and Cassiopeia in the original Battlestar Galactica (1978);[19] I would also note the use in that series of the Zodiac to denote the Twelve Human Colonies.

Another example came be drawn from the Planet of the Apes franchise. There the characters played by Roddy McDowall are called 'Cornelius' in Planet of the Apes (1968), Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) (though there the character was played by David Watson), and Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), 'Caesar' in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) and Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973), and 'Galen' in the Planet of the Apes television series (1974). This is, it must be admitted, a slightly problematic case. Caesar appears in two films that take place in what was then the near future, when there would still presumably be access to Roman history. Though in the others knowledge of human history has been lost by the apes, it remains possible that some names might survive. However, this example does illustrate the way genuine Latin names can then be supplemented by ones with a pseudo-Latin feel, such as the orang-utan Dr Zaius in Planet ... and Beneath ....[20]

For an example where Classical sources have been used to help imagine an entire culture that can have no connection with those sources, we can go a long, long time ago to a galaxy far, far away. I am, of course, talking about Mike Butterworth and Don Lawrence's classic comic, The Trigan Empire, which has been described by Neil Gaiman as 'the story of something a lot like an SF Roman Empire on a distant planet'.[21] It is in fact a great deal more, and Butterworth and Lawrence used popular views of the Greeks, Mongols and Saharan nomads to populate the planet of Elekton. But it is the sf Augustus, Trigo himself, and the Roman trappings of his empire, that are always remembered.

It is also the case that George Lucas' Star Wars films (commencing in 1977 with Star Wars) take much of their political terminology (Republic, Empire, Senate, etc.) from Rome, and even the broad outline of the galaxy's political history (the change from Republic to Empire). Some of this has come via the influential Foundation novels of Isaac Asimov, which helped establish the popular space opera trope of the Galactic Empire, and themselves draw upon two Classically-related sources, Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-88) and Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War.[22] But not all of the Roman elements in Lucas' work have come from Asimov. Lucas may not have consulted any Classical sources or works on Roman history himself, but he is clearly familiar with cinematic interpretations of Rome's past.

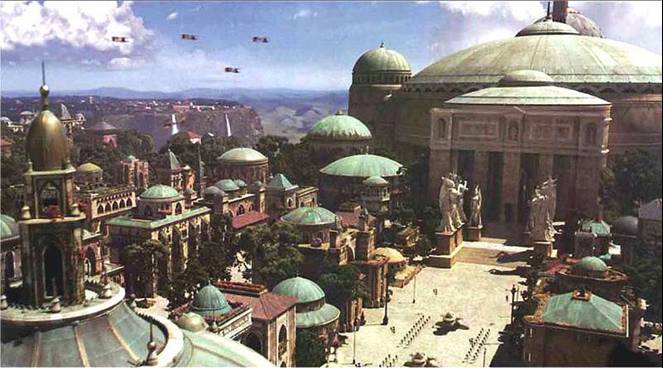

This is shown if we move from the sublime to the ridiculous, which in this case means moving from Episodes IV-VI of the Star Wars series to the more recently made Episodes I-III. In The Phantom Menace (1999), not only does the capital of the planet of Naboo draw its appearance partly from many reconstructions of ancient Rome, as well as being reminiscent of the modern city (and other cities such as Istanbul); but a triumphal sequence at the end is stolen shot-for-shot from Commodus' arrival in Rome from Anthony Mann's Fall of the Roman Empire (1964).[23]

Above: Naboo, from Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999).

Below: Reconstruction of the Roman Forum.

This sort of reception in sf through a previous reception can also be seen in the Doctor Who story The Robots of Death (1976).

The robot face illustrated here derives ultimately from a Greek comic mask[24] (itself presumably influenced by the archaic kouros). But the production designer for Doctor Who has gone not to Greek originals, but to the appropriation of Greek objects by the Art Deco movement.

Stealing

My next category is one step up from borrowing - stealing. Here not just elements of the background or foreground have been taken from an ancient culture, but the story itself derives from a Classical original. This approach is, of course, not unique to sf. Two non-sf examples are James Joyce's Ulysses (1922), and the Coen Brothers' movie O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), both of which take Homer's Odyssey as their source text (though both depart from it considerably).[25]

In sf there is Brian Stableford's Dies Irae trilogy (The Days of Glory, In the Kingdom of the Beasts and Day of Wrath, all 1971), which draws heavily upon the Iliad in its first volume and upon the Odyssey in its second. The Odyssey is again used in R.A. Lafferty's novel Space Chantey (1968).[26] Robert Silverberg's The Man in the Maze (1968) is a retelling of Sophocles' play Philoctetes, even retaining Lemnos as the name of the planet to which his Philoctetes-equivalent has been exiled.

The use of the term 'stealing' is not necessarily meant to pass any judgement on the merit of works that take this approach. Some, such as Joyce's novel, are high art. However, sometimes stealing (or indeed borrowing) seems to encourage a laziness in writing, a sense that all the work has already been done for the writer, so they needn't bother. There are two Doctor Who stories from the late 1970s that exemplify this. One, Underworld (1978), is a reworking of the Jason and the Argonauts myth; the other, The Horns of Nimon (1979), retells Theseus' adventure in the Cretan Labyrinth. Neither is very good, and through the use of anagrams for names (for instance, Herick and Tala for Heracles and Atalanta in the first, and Aneth and Skonnos for Athens and Knossos in the second) come close to insulting the intelligence.[27] (I said earlier that reception studies allows one to revisit favourite works of art and media, but sometimes you have to watch The Horns of Nimon again.)

Ghosting

At Nick Lowe's suggestion, I have added a final category, ghosting. This covers stories where no direct influence of classical originals can be established, but where nevertheless there are strong hints of themes derived from antiquity. Once could in this category talk of the possible influence of the Jason myth upon 2001 - both are stories in which an adventurer goes beyond the limits of the known universe in order to recover wondrous artefacts. However, this category is inherently nebulous, and such connections can be difficult to establish. Moreover, one can start to see them everywhere, especially since, as most recently demonstrated by Simon Goldhill in Love, Sex and Tragedy (2004), western civilization is deeply rooted in the Classics.

That concludes my tentative framework. It oversimplifies, breaks down when applied to examples that cross the boundaries, and may be of little use to anyone else - but I find it useful for myself and for my work.

Given western civilization's roots in the Classics, it is inevitable that Classical references will be found throughout sf, and no study can hope to cover them all. But I believe that looking at how the two areas interact can be valuable for both. For Classics and science fiction are both areas that can be used to put a comforting distance between subject and audience.[28] It can be easier to comment on modern imperialism if you take as your background the Peloponnesian War or the far future.

It's worth noting the differences, though. Edith Hall has pointed out to me that Joyce in particular, and others, use the Classics as a peg of familiarity in order to allow himself to write a more avant-garde literary work. Derek Walcott does something similar when he uses the Odyssey for his ambitious poem Omeros. Sf, on the other hand, tends not to do this, as the genre can often be conservative in terms of literary form, and is already attempting to get its readership to buy into novel ideas, and cannot always afford to load novel structure upon that.

Nevertheless Classics will continue to be received in science fiction[29] - and indeed my next reading matter is Stephen Baxter's new novel Emperor (2006).

Appendix

Stephen Baxter, Coalescent (2003), pp. 372-3

Notes

[1] Technically not until mentioned on-screen in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991).

[2] Writers of 'slash' fanfiction featuring the unspoken love between Kirk and Spock (of whose work Roddenberry was presumably aware) might take such a statement as evidence that they were right all along.

[3] Soldier of the Mist (1986) and Soldier of Arete (1986), both set in the early fifth century BC.

[4] Where there is a science fictional element, however, such as in the Star Trek episode 'Who Mourns for Adonais?' (1967), or the use of gods in superhero comics, which are inherently science fictional milieus, then, of course, I am interested.

[5] I discuss deeper Homeric themes in 2001 in a paper entitled 'Odyssey or Argonautica? Classical themes in the "proverbial good science fiction film"', to be delivered at the 2006 Eastercon.

[6] I agree with the publisher - I, Robot is a much better title.

[7] Since classical names have been given to the planets, constellations and many stars, such names abound in those sections of sf that deal with space exploration (e.g. Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars novels). Similarly Greek and Latin are hardwired into the language of science, and therefore into the language of science fiction. But one cannot cover these in detail as classical receptions in their own right - that way madness lies.

[8] It should be noted that Laumer gives a fin de siecle/Edwardian feel to his descriptions of the Imperium, and Valigursky may actually be referencing c. 1900 imitations of Roman attire. Incidentally, Damon Knight's cover quotation is quite curious, as the novel contains no time travel whatsoever.

[9] See Andrew M. Butler, Philip K. Dick (Pocket Essentials, 2000).

[10] As revealed in MacLeod's 2006 Guest of Honour speech to the sf convention Boskone, available on his weblog: http://kenmacleod.blogspot.com/2006_03_01_kenmacleod_archive.html.

[11] Rather more knowledge of Plato is shown in the 1972 Doctor Who story The Time Monster, where minor characters have the names of Platonic dialogues.

[12] The stories referred to are The Romans (1964), The Myth Makers (1965), The Time Monster (1972), The War Games (1969) and The Mind Robber (1968). For relevant spin-off stories, see, e.g., Christopher Bulis' novel State of Change (1994), set around the time of Cleopatra, or the Big Finish audio story The Council of Nicaea (2005).

[13] In a paper entitled 'Little Iliads: Dramatising Homer from Rhesus to Troy', delivered at the Greenwood Theatre, 10 February 2005, immediately prior to a performance of the pseudo-Euripidean Rhesus.

[14] For my own views on the relationship between Troy and Greek mythology, see 'Troy: a reflection', http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/classtud/troy/keen-troy.htm.

[15] Sic. I assume the corruption of Latin is a publisher's doing rather than Silverberg's.

[16] Neville Morley, 'Trajan's Engines', Greece and Rome 47 (2000), pp. 197-210.

[17] I owe this observation to Dr Eleanor OKell.

[18] The sequence began with The Pastel City (1971). The stories are collected in Viriconium (2000, reissued in 2005 with an introduction by Neil Gaiman).

[19] 'Pandora and the Pythia: Classics meets 9/11 in the current US TV Series Battlestar Galactica'.

[20] The Roman references are continued in Tim Burton's 're-imagining' of Planet of the Apes (2001), where the ape city is ruled by a Senate.

[21] In 2003: http://www.neilgaiman.com/journal/archive/2003_12_01_archive.html.

[22] Foundation (1950, fixup of stories originally published in Astounding Science Fiction 1942-44), Foundation and Empire (1952, stories in ASF 1945), and Second Foundation (1952, stories in ASF 1945). For the classical roots of the series, see Martin M. Winkler, 'Star Wars and the Roman empire', in Martin M. Winkler (ed.), Classical Myth and Culture in the Cinema (2001), pp. 272-90, with further references therein.

[23] It's known that during the making of Star Wars, before the special effects sequences had been filmed, Lucas used footage from WWII air combat films cut with what he had shot to illustrate how the final film would appear. I suspect the same technique was used for the triumphal scene in Phantom Menace, with Lucas recutting Mann's film to show Industrial Light and Magic what he wanted from this CGI sequence.

[24] This observation is also owed to Eleanor OKell.

[25] One could also mention poetic reworkings of classical authors, such as the anthology After Ovid (1995, ed. Michael Hofmann and James Lasdun), or Maureen Almond's transpositions of Horace into twentieth century Teesside (in The Works, 2004).

[26] Brian Stableford, in the entry on 'Proto Science Fiction' from John Clute and Peter Nichols, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1993, corrected edition 1999) notes at least five sf versions of the Odyssey (p. 966).

[27] Compare also Asimov's transparent lifting of Belisarius as 'Bel Riose' in Foundation and Empire (1952).

[28] For the use of Classics in this way, see Lorna Hardwick, Reception Studies (2003), especially Chapter VI.

[29] Not least because of those sf and fantasy writers who have Classical backgrounds - e.g. Adam Roberts has a degree in English and Classics, Juliet McKenna one in Classics, and Harry Turtledove wrote a Ph.D. in Byzantine history.

Introduction number one: Studying the way that Classical antiquity is received in modern works of art and literature changes not only the way we look at those works, but also how we look at the source material. For instance, many of my thoughts on what Athenian dramatists were actually trying to say have been formed or amplified through observation of contemporary interpretations. Sometimes the insights are quite unexpected - it wasn't until I read Ulysses, and saw what Joyce was trying to do, to find the exact combination of English words that conveyed the precise nuance that he desired, that I finally understood what Thucydides was trying to do with Greek. And so it is with science fiction.

Introduction number two: I am aware that in looking at science fiction, I am in danger of being perceived to be engaged in the study of the 'banal and quotidian' that Charles Martindale condemned in the Reception debate at the 2005 Classical Association Conference in Reading. The frivolous response to such a charge would be to say that I'm just using this as an excuse to read all the books and watch all the television and films I would read and watch anyway, and call it 'research'; but that would be rather to denigrate my own work, and potentially that of everyone else working in reception. So instead I shall defend myself from such a charge in two rather more serious ways. First of all, sf is not intrinsically banal and quotidian. (I'm not going to argue this - it just isn't.) Secondly, even if it was, it wouldn't matter. Martindale's objection, in my view, confuses aesthetic value with cultural significance. I have no objection to people making aesthetic judgements, and make plenty of my own. But any such judgement I or others might make is unrelated to whether the piece of work judged is worthy of study in terms of its reception of Classical ideas. Put simply, one can say that Gladiator is a poor film, but it doesn't follow from such an opinion that Gladiator is not important. If most people are getting their experience of the ancient world through the banal and quotidian, then it is the banal and quotidian that must be studied.

Let us start then, as an example of how sf receives the classics, with Tiberius. Not the second Roman emperor, stepson and adopted son of Augustus; but arguably the single most iconic figure in all of science fiction, Star Trek's James Tiberius Kirk.

Captain Kirk's middle name took a long time to be established. Indeed, when he was first introduced, in the second pilot of Star Trek, 'Where No Man Has Gone Before' (1966), his middle initial is shown on a gravestone as 'R.' This detail had been forgotten by the next time someone wanted to give Kirk's middle initial, and so it became 'T.' But what this stands for remained unknown throughout the original run of Trek.

That it is 'Tiberius' was finally established in 1974, in an episode of the animated series of Star Trek that followed the original - 'Bem', written by David Gerrold. Now, almost everything that happened in the animated episodes is considered non-canonical for subsequent Trek productions. That is, they are never referred to, and no attempt is made to avoid contradicting them. But, curiously, the detail of Kirk's middle name does get into the Star Trek canon.[1] This suggests to me that it was series creator Gene Roddenberry's notion, rather than writer Gerrold's.

In the novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), there is a preface made out to be by James Kirk himself. (The novelization is credited to Roddenberry, but reportedly is actually by Alan Dean Foster, so what we have here may be Foster pretending to be Roddenberry pretending to be Kirk.) In that preface, Kirk shows his Classical credentials by stating that he has come to be seen as a new Ulysses, and that he is uncomfortable in the role. He also explains his name:

My name is James Tiberius Kirk. Kirk because my father and his male forebears followed the old custom of passing on a family identity name. I received James because it was both the name of my father's beloved brother as well as that of my mother's first love instructor. Tiberius, as I am forever tired of explaining, was the Roman emperor whose life for some unfathomable reason fascinated my grandfather Samuel.

Anybody who has read Suetonius' Life of Tiberius, or is familiar with I, Claudius or Tinto Brass' 1979 film Caligula, will know that Tiberius was notorious for the quantity, variety and invention of his sexual perversions. Several questions therefore clearly arise. What exactly was it about Tiberius that so fascinated Samuel Kirk? Do Samuel Kirk's interests, together with James being named after his mother's 'love instructor' (whatever one of those is), explain the voracious heterosexual appetite of the grandson?[2] But above all, what were they thinking?

I'd now like to examine some theoretical models. Greco-Roman elements (or indeed elements from any historical culture) can be used in science fiction in a number of different fashions. What follows is a rough framework for discussion, and is not meant to be a rigid categorization of use of Classical elements, but a broad heuristic tool. It is a model, and like most models, breaks down when subjected to rigorous examination. And I remain firmly in the camp of those who would rather break the model than break the evidence.

Retellings

Straight retellings of mythological tales don't really interest me for the purposes of this paper or for the larger work. These stories, such as Weight (2005), Jeanette Winterson's recent reinterpretation of the Atlas myth, belong in the genre of fantasy rather than sf (where they do not, as David Gemmell's bestselling Troy: Lord of the Silver Bow [2005] does, belong in historical fiction). Of course, the boundaries between sf and fantasy are frequently blurred, as anyone familiar with the works of China Mieville will know. But I don't have time to go into a detailed discussion of the definitions of both genres, which would in any case only be my definitions, and would not necessarily be recognized by everyone. Let me just say that, in my view, science fiction assumes a rational explanation to everything, no matter how fantastic it might seem or how pseudo-scientific that explanation might be, whilst fantasy assumes the irrational. So, gods that are in fact super-powerful aliens are science fiction, gods that are gods belong in fantasy. And to this latter category we must consign, as well as retellings, new tales featuring mythological characters, such as the various different film and television series featuring Hercules, stories featuring new characters in a mythological past, such as Xena: Warrior Princess, tales of the fantastic set in historical antiquity, such as Gene Wolfe's Latro in the Mist novels,[3] or even tales of the gods still walking amongst us, such as the episodes of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, 'Yes Virginia, There is a Hercules' (1998) and 'For Those of You Just Joining Us' (1999), where there is no science fictional element.[4]

What are the truly science fictional uses?

Allusion

First is simple allusion, brief references to ancient history or literature that are not particularly central to the story being presented. This can manifest itself in titles, without carrying any deeper message. Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1934 story 'A Martian Odyssey', that later gave its name to a collection of his stories from 1949, has little in common with Homer's epic poem beyond both being about long journeys. The same appears to be true, at least on the surface, of Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.[5]

Such title allusion can sometimes be not to the Graeco-Roman originals, but to other receptions, such as when Eando Binder (Earl and Otto Binder) entitled their short story 'I, Robot' (Amazing Stories, January 1939), referring to Robert Graves' classic 1935 novel I, Claudius. (The title was later stolen by Isaac Asimov's publisher for the first collection of Asimov's own robot stories in 1950, much to Asimov's annoyance, as he preferred Mind and Iron.)[6]

Allusions may be in the sf work in the form of names,[7] such as James Tiberius Kirk already mentioned; or the use of terms like 'imperium', as in Keith Laumer's Worlds of the Imperium, where the Imperium is the name of the principal state in the story.

In the latter case, as seen above, the name of that state may have inspired cover artist Ed Valigursky to put Roman-style helmets on the figures illustrated.[8]

More substantially, classical allusion may be used to comment on the situation in which the characters find themselves. One such may be found in an episode of the sequel to Star Trek, Star Trek: The Next Generation, 'Best of Both Worlds' (1990). Faced with the Borg, an implacable enemy that may destroy the Federation, Captain Jean-Luc Picard muses on whether this was how the emperor Honorius felt in AD 410 as the Goths descended upon Rome. The purpose of the allusion is not always so immediately clear. In Ken MacLeod's novel The Stone Canal (1997), two drunk men sit by the Forth Estuary and talk about how this is where Rome stopped (a reference in keeping with the theme of the Newcastle conference, 'On The Frontier'). The immediate significance of this isn't apparent on first reading, though there does seem to be something of a meme in recent British literary sf of scenes with two blokes drinking and talking about the Roman empire - in an appendix I've included a similar scene from Stephen Baxter's Coalescent (2003), though there it's more obviously relevant, as the story begins in early fourth century AD Roman Britain. This meme may go back to the American author Philip K. Dick, whose characters, as the sf critic Andrew M. Butler has shown,[9] often muse on Rome - even before Dick's (presumably drug-induced) visions of being himself transported back to the late first century AD.

However, MacLeod is a man with interests in classical antiquity - he is well-versed in the Epicureans and Stoics and the works of Lucretius and Marcus Aurelius[10] - so the reference in his case is unlikely to be gratuitous. As one reads The Stone Canal further, it becomes clear that the novel is very interested in the limits of empire, and that may be why MacLeod has included this scene.

These allusions make important points about popular understanding of antiquity. Classicists know that Honorius was actually in his capital Ravenna at the time of the sack of Rome, but the writers of Star Trek clearly don't. Ken MacLeod probably does know that to say that Rome stopped at the Antonine Wall is an oversimplification that ignores the Flavian, Antonine and Severan penetrations further into Scotland; but his characters, two drunk blokes talking shite, can't necessarily be expected to have that knowledge.

Appropriation

A step up from allusion is appropriation, the depiction of a society or individual which has in some method consciously modelled itself upon Greco-Roman (or other historical) precedents. For examples of this I turn once again (but for the last time) to Star Trek. A non-classical instance is the episode 'A Piece of the Action' (1968), in which a planetary culture is encountered that imitates Chicago mobsters of the 1930s. 'Plato's Stepchildren' (1968) provides a classical example. This episode was controversial in the United States because it reportedly featured the first depiction of an interracial kiss on network television, and was banned in the UK, probably because of a sado-masochistic whipping scene that suggests Jim Kirk may know more about his grandfather's fascination with Tiberius than he's letting on. But my interest in it is because it features a society that has allegedly modelled itself upon Plato's ideal state. However, I doubt Plato ever envisaged his philosopher kings as being in addition super-powerful psychokinetics, and I also doubt that the episode's writer, Meyer Dolinsky, had read much Platonic philosophy - certainly there's little sign of it in the episode.[11]

Allusion aside, appropriation is far and away the most plausible form of reception of the Classics in sf, as it is simply imagined societies and individuals doing what real historical cultures, such as Napoleonic France or Fascist Italy, did. However, it is also one of the least common. Nazis seem to be much more popular for this sort of story (q.v. Star Trek, 'Patterns of Force' [1968]).

Interaction

More frequent is what I call, perhaps somewhat misleadingly (and not necessarily in honour of the 2005 Worldcon), interaction. This covers stories actually featuring the cultures or individuals (real or imagined) of the Classical past, or some continuation of the same. The locus classicus for this sort of tale, of course, is the long-running BBC television series Doctor Who, a show based around the concept of travel in time and space (in the unlikely event that there's any one reading this who doesn't know that). And indeed, the Doctor has on his travels visited Rome at the time of Nero, the Trojan War, and the pre-Hellenic Aegean in the age of Atlantis, and encountered displaced Roman soldiers and creatures of Classical mythology; and more such stories are to be found in spin-off novels and audio dramatizations.[12] But interaction can be seen elsewhere. There are two consecutive 1974 stories from ITV's 1970s rival to Doctor Who, The Tomorrow People. In the second, A Rift In Time, the Tomorrow People travel back to the Roman period (and inadvertently interfere in human history by bringing about the Industrial Revolution a thousand years too early, forcing them to go back and put it right). In the first, The Blue and the Green, more unusually, they find themselves up against entities which promoted the rivalry between factions in the Roman circus. For a literary example, Stephen Baxter's Coalescent, already mentioned, concerns a secret society whose origins lie in fifth-century AD Rome. Or one might encounter a Princess who comes from among the Amazons, who have kept themselves sealed off from Man's World for millennia (the origin of William Moulton Marston's superheroine Wonder Woman).

It is in these sorts of stories that I think one can start to see what science fiction can do that other forms of reception perhaps can't as easily.

As an example, I take Helen of Troy. Casting Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, is very difficult for a naturalistic stage, film or television production, since beauty is such a subjective concept. My favourite exemplar of this is Michael Cacoyannis' film of Euripides' Trojan Women (1971). Cacoyannis cast Irene Pappas in the role, who was his wife, and therefore his idea of perfection in female beauty. But she's not mine, especially not when the same film features Vanessa Redgrave at her most radiant in the role of Andromache. When Doctor Who tackled the Trojan War, in a 1965 story called The Myth Makers, writer Donald Cotton solved this problem simply by never bringing Helen on screen, and thus her appearance always remains in the viewers' imaginations. Now, it might well be said that any writer of historical fiction could pull the same trick, but I'm not sure that a non-sf treatment would think to exclude Helen in this way. More likely they would take the approach of Eric Shanower's series of graphic novels Age of Bronze (1998 onwards), where Helen's supreme beauty is a rumour spread by Odysseus to motivate the Greek army. This is a realistic approach, but for me lacks the elegance of Cotton's trick. However, the trick is not unique to sf, as Hector Berlioz in the nineteenth century omitted Helen from the onstage cast of Les Troyens, and it may well have been this which gave Cotton the idea.

If the example of Helen is something that genres other than sf can do, then a convincing portrayal of the Greek gods is much more sf's province. Nick Lowe has observed[13] that almost all recent treatments of the Trojan War have excluded the direct involvement of the gods, either through eliminating them entirely or through segregating them from the principal human characters. This is true not just of Wolfgang Petersen's film Troy (2004), which was much criticised for this aspect (as well as others),[14] but also of Shanower's Age of Bronze and Gemmell's Troy, and (as far as I am aware) of Lindsay Clarke's The War At Troy (2004) and Valerio Massimo Manfredi's The Talisman of Troy (2004). According to Lowe, the only recent treatment of the Trojan War to successfully integrate the gods is Dan Simmons' sf novel Ilium (2003; the sequel, Olympos appeared in 2005). There advanced technology takes the place of the divine power that seems to embarrass other writers interested in writing historical adventures; the gods' Mount Olympos becomes Olympus Mons on Mars.

Into this category I would also put stories dealing with alternate histories (or 'counterfactuals' for authors worried that they might otherwise be accused of writing science fiction), e.g. ones where Rome never fell. The two characters in Baxter's Coalescent are discussing what might have happened had the western Roman empire survived, and such a notion is at the heart of Robert Silverberg's Roma Eterna[15] (2003), and of Sophia McDougall's recent Romanitas (2005). In Silverberg's collection of stories, the combined factors of the Jewish Exodus from Egypt ending in disaster, and a different emperor succeeding Septimius Severus, lead to the survival of the Roman empire past the twentieth century.

Alternate history, to my mind, makes us ask new questions of the ancient world. Classicists often look at, for instance, how the Roman empire worked, but less often, I feel, at questions of whether the Roman empire was a good thing or not. Would we want it to survive? Would we want to live in a state which, though it brought order and peace, was a slave-owning military dictatorship where freedom to criticize the government was severely limited? Looking at alternate histories prompt us to ask such questions, even if they were not always in the original authors' minds.

Sometimes the connection between alternate history and scholarship can be even closer, and alternate history can take on the form of academic discourse, as in Neville Morley's brilliant paper to the 1999 Classical Association Conference, subsequently published in 2000 in Greece and Rome - 'Trajan's engines', a scholarly examination of technological feats the Romans never actually achieved.[16] So well done is this that some were fooled, and it still crops up in some online bibliographies of writing on Trajan.

Borrowing

My fourth category, borrowing, is much like appropriation, in that elements of Classical antiquity are used to build an imagined society. The difference is that in this case only the author and audience are aware of the origins of features of the imagined culture - the members of the culture themselves are not, and cannot be, for there is no connection between them and Earth's antiquity.

Sometimes this borrowing can be as minor as simply the use of nomenclature. Greek and Latin can be a reliable source of names that are sufficiently unfamiliar to a readership to be credibly alien, yet retain the ring of something that might actually be spoken, rather than something that an author has made up off the top of his head. This is especially the case where a name does not conjure a particular individual in the popular imagination.[17] M. John Harrison takes the Roman name of Wroxeter, Viriconium, for a fictional city at the centre of a sequence of what are strictly speaking fantasy stories, but ones with a strong sf undercurrent.[18] In the paper that formed the other part of the panel in which the current paper was presented, Amanda Potter commented on the use of names like Apollo, Athena and Cassiopeia in the original Battlestar Galactica (1978);[19] I would also note the use in that series of the Zodiac to denote the Twelve Human Colonies.

Another example came be drawn from the Planet of the Apes franchise. There the characters played by Roddy McDowall are called 'Cornelius' in Planet of the Apes (1968), Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) (though there the character was played by David Watson), and Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), 'Caesar' in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) and Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973), and 'Galen' in the Planet of the Apes television series (1974). This is, it must be admitted, a slightly problematic case. Caesar appears in two films that take place in what was then the near future, when there would still presumably be access to Roman history. Though in the others knowledge of human history has been lost by the apes, it remains possible that some names might survive. However, this example does illustrate the way genuine Latin names can then be supplemented by ones with a pseudo-Latin feel, such as the orang-utan Dr Zaius in Planet ... and Beneath ....[20]

For an example where Classical sources have been used to help imagine an entire culture that can have no connection with those sources, we can go a long, long time ago to a galaxy far, far away. I am, of course, talking about Mike Butterworth and Don Lawrence's classic comic, The Trigan Empire, which has been described by Neil Gaiman as 'the story of something a lot like an SF Roman Empire on a distant planet'.[21] It is in fact a great deal more, and Butterworth and Lawrence used popular views of the Greeks, Mongols and Saharan nomads to populate the planet of Elekton. But it is the sf Augustus, Trigo himself, and the Roman trappings of his empire, that are always remembered.

It is also the case that George Lucas' Star Wars films (commencing in 1977 with Star Wars) take much of their political terminology (Republic, Empire, Senate, etc.) from Rome, and even the broad outline of the galaxy's political history (the change from Republic to Empire). Some of this has come via the influential Foundation novels of Isaac Asimov, which helped establish the popular space opera trope of the Galactic Empire, and themselves draw upon two Classically-related sources, Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-88) and Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War.[22] But not all of the Roman elements in Lucas' work have come from Asimov. Lucas may not have consulted any Classical sources or works on Roman history himself, but he is clearly familiar with cinematic interpretations of Rome's past.

This is shown if we move from the sublime to the ridiculous, which in this case means moving from Episodes IV-VI of the Star Wars series to the more recently made Episodes I-III. In The Phantom Menace (1999), not only does the capital of the planet of Naboo draw its appearance partly from many reconstructions of ancient Rome, as well as being reminiscent of the modern city (and other cities such as Istanbul); but a triumphal sequence at the end is stolen shot-for-shot from Commodus' arrival in Rome from Anthony Mann's Fall of the Roman Empire (1964).[23]

Above: Naboo, from Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999).

Below: Reconstruction of the Roman Forum.

This sort of reception in sf through a previous reception can also be seen in the Doctor Who story The Robots of Death (1976).

The robot face illustrated here derives ultimately from a Greek comic mask[24] (itself presumably influenced by the archaic kouros). But the production designer for Doctor Who has gone not to Greek originals, but to the appropriation of Greek objects by the Art Deco movement.

Stealing

My next category is one step up from borrowing - stealing. Here not just elements of the background or foreground have been taken from an ancient culture, but the story itself derives from a Classical original. This approach is, of course, not unique to sf. Two non-sf examples are James Joyce's Ulysses (1922), and the Coen Brothers' movie O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), both of which take Homer's Odyssey as their source text (though both depart from it considerably).[25]

In sf there is Brian Stableford's Dies Irae trilogy (The Days of Glory, In the Kingdom of the Beasts and Day of Wrath, all 1971), which draws heavily upon the Iliad in its first volume and upon the Odyssey in its second. The Odyssey is again used in R.A. Lafferty's novel Space Chantey (1968).[26] Robert Silverberg's The Man in the Maze (1968) is a retelling of Sophocles' play Philoctetes, even retaining Lemnos as the name of the planet to which his Philoctetes-equivalent has been exiled.